Refuse, Reduce, Reuse, Recycle – four

things that most architecture students subscribe to, but find very

hard to put to practice in the architecture studio.

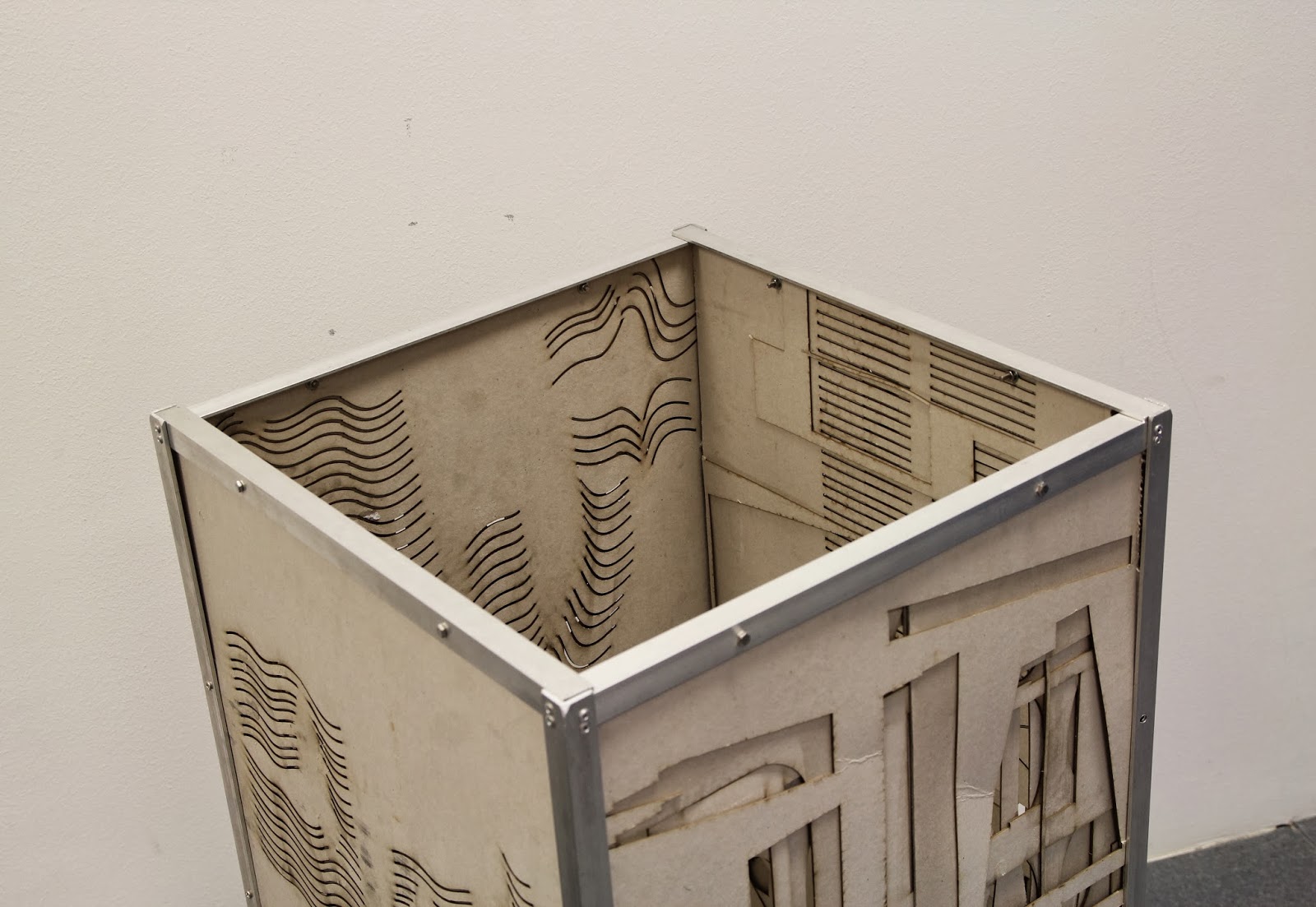

This box-on-wheels was a personal

experiment to see how far one could push the term 'reuse' in the

context of the studio. Most of our models are built using cardboard

parts that are precision cut by a laser. However, weird geometries

combined with time pressure limit how much cardboard we can save by

arranging the parts efficiently.

Inspired by the use of cardboard as

structural element in product design (furniture, bicycles), I came up

with the idea of laminating/gluing multiple sheets of scrap, lasercut

cardboard sheets together to form a relatively strong board which

could be reused. In addition, I also believed that the interesting

shapes and uniqueness of each board would lend an aesthetic touch to

the final product.

The box would comprise of an aluminum

frame with wheels and the sides and bottom of the box would be made

out of up to 8 layers of laminated scrap cardboard. Scrap cardboard

was plentiful in the studio and I chose pieces that still had a

relatively large amount of cardboard on them. The boards with more

interesting designs were earmarked to form the front and back of the

laminated board. Gluing the boards was a messy business that drew the

curiosity of my studio mates!

The final product was rather heavy. The

laminated cardboard turned out to be relatively solid as a material,

and I believe that the back and sides will hold up to anything that

is not too heavy (3kg on each side, 40kg spread out on the bottom,

which has bracing). As of now, the box would be used as a protective

container to store my architecture posters!